The YF-19 Project

Dedicated to all Pioneers...

Surrounded by snacks and all sorts of unhealthy foods, me and my friends from High School sat down one summer evening to watch our recently acquired VHS finding: A 1995 series of OVA (Original Video Anime) called Macross Plus. We hit the play button, and this message begins the film:

Dedicated to all pioneers…

A 1/48 scale model of the YF-19 made by Hasegawa

I don’t have enough words, nor I would finish anytime soon, to express how much this movie meant for me, and means to me ever since. The main story is a love triangle between Isamu, his teenage years sweetheart Myung and his best buddy Gold. But really, the stars of this film are the planes, the YF-19 and the YF-21, who are competing for the next production contract for the UN Spacy to create the next generation Variable Fighter and replace the aging VF-11. This was based on an actual competition in the US between the YF-22 from Lockeed Martin and the YF-23 from McDonell Douglas, from which the YF-22 won and got the contract to produce the next-gen fighter F-22 Raptor.

Clearly inspired by the YF-23, the YF-21 in Macross Plus is test piloted by Gold, who uses an experimental mind-driven control and visualizes the plane in full VR like it was his own body. Isamu, on the other hand, pilots the YF-19, based on the experimental forward winged X-29 and the recently revealed SU-47, with traditional controls, but with enhanced maneuverability and vision with a screen-projected exterior inside his cockpit.

Very few things have resonated so much in my head when watching a movie. This one became my favorite Anime film of all time ever since. Yoko Kanno, the composer for this film, became my favorite Japanese animation musician of all time. Shōji Kawamori , the designer behind the vehicles became my favorite designer and so-on-so-on.

Anyway, I used to daydream a lot about this plane and how would it be like to be in its cockpit, looking out through these screens that evolve the whole sky as a single thing and make you feel like you’re flying as a bird. My love for flight simulators and Sci-Fi was fueled by technologies like this. So eventually, when I started learning Blender, a single question raised up:

Wouldn’t it be awesome to finally find out what it looks like?

So the YF-19 project was born.

(Also known as the series of Early Big Bad Mistakes)

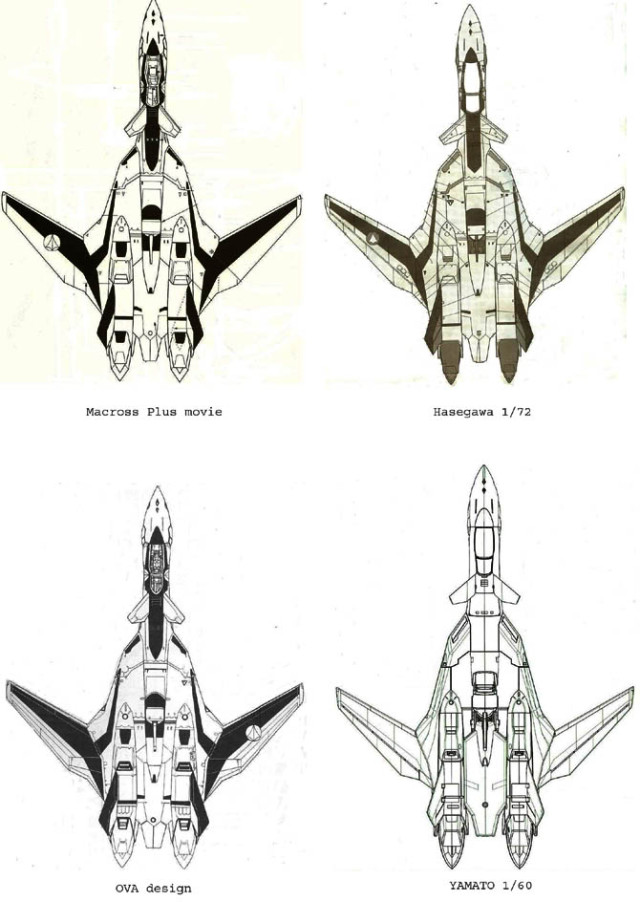

As I was gaining experience in modelling in Blender I started getting myself a pretty decent amount of reference material. Besides the Movie and the OVAs, I had three basic sources of information for the YF-19: The Hasegawa 1/48 scale model (which I own one but I haven’t got myself time apart to build it), the Arcadia 1/60 transformable toy, and CG models from people around the globe. I went to the usual image search sites, like Google Images, but also scrolled down Deviantart.com, Tumblr, Pinterest, Bing, the Macrossworld forums and tons other anime galleries. I got essential information about the plane, its dimensions, weight and thrust rate, color variants, versions and above all, the source material for the films, which is a bunch of amazing sketches and designs by the franchise senior designer, Shōji Kawamori.

Turns out there are these many variations of the same exact plane.

Many many reference images.

After choosing precisely what views were the most eloquent with each other, I formed a basic viewport and started creating the nose shape, while still digesting the most of what Youtube had to say about Blender. I took this snapshot on July 28, which is my birthday! This shows how committed I was to this new project, I had to model and take snapshots instead of eating cake or whatever people do on their birthdays.

Once I understood the basics on modelling in Blender, it was just a matter of recovering all my seemly lost memories about the art of 3d modelling something.

First modelling attempt in Blender.

As I was creating the next piece of mesh, I started getting the hang of it quicker and quicker. I could remember these things! How to keep four sided patches at all times, how to move topology away to make holes like the front romboidal openings on the nose, it was all getting surely but gradually back.

I started cutting pieces and extruding them separately to make the panel divisions, while stretching new extrudes and “wrapping” the fuselage around. There was no time to lose, this was me modelling again!

The way I’ve been cutting these panels from the mesh has been basically, start with the whole section, then subdivide and cut it, add as many vertexes as i need to sharpen the edges between the panels when smoothing the whole thing, and so on. Since my cousin is a programmer, he wanted to know how many polygons the plane had already. I looked at the Blender info section and quickly responded: 120,000!…. Whoa….

120,000 polys.

“So, would that be too much for a video game?”, I innocently asked. “Yup”, was his short answer.

You see those triangular shapes at both sides of the fuselage? Well, on closer inspection, there should be only one of them, on the left. As far as I know, they’re some sort of micro-missile hidden door or something.

Right there.

So no big deal, right? It’s just a matter of not using mirror here, creating the whole piece as a single thing and then deleting the right side panels, reconstructing the mesh and keep on. But that little thing got me thinking: Why am I carving out each and every single panel out, even ones that are not probably panels but part of the paint job? (the zig-zaggy line above that triangular cut is probably a division with a grey paint job on top of it) Wouldn’t there be a more poly-efficient way to get the result I want without carving all of this? And with a plus: I could reduce the poly number substantially.

When my cousin commented on the last close-up above that the “UV mapping will be a nightmare”, I had to agree. Not only I had no idea how to UV map something in Blender, I was making it a lot more difficult if you could just make a bump map with the panel lines, UV map the surface and call it a day. Plus, I was going all the way down with this plane into a realistic short film of some kind, so I wanted efficiency of method in the model and let the textures and lighting do the rest. The idea of loading an extremely heavy model into a scene to be rendered, instead of a light, efficient model with the right UV maps and textures, was starting to become a daunting thing.

The last nail on the coffin for this stage of construction was that I had been watching a lot of pictures and videos on the Arcadia transformable toy, and I was getting more and more inspired to not only animate the YF-19 as a plane, but as a GERWALK and Battroid. That involves critical thinking in the modelling process, since from the beginning the modelling would have to divide the fuselage into the parts that disassemble and form the robot. It was a very exciting idea, and nowhere near the initial plan of just learning how to model something in Blender.

The YF-19 project had to make a forced landing here, and get back to the drawing board… plus watching loads of new tutorials.

After a few tutorials I was able to go back and re-do the whole plane all over again, but this time I took special care to economize on the polycount, use a feature in Blender that creates creases without the need for extra loops and mesh, and overall take the extra step into the detail to get as close as possible to the Hasegawa scale model.

This time, however, the idea was to make it transformable, so from the modelling point I started dividing it in different parts, using the fuselage panel lines and the toy as a reference of which parts are separate when transforming.

Pretty much everything else that was modeled belongs to the Mechanical area: the arms, hands, head and parts that are mostly hidden in the plane mode, but that unfold to create the robot versions like GERWALK and Battroid. It also means I had to learn how to rig this so I could control it.

There was not much information about this part so I reduced the segments to make it look closer to the toy's.

We enter the new undiscovered world of textures and materials, where I had pretty much no experience, practice, or idea of how to do anything. This took the most time for me but became one of the most enjoyable parts of creating this plane.

This whole journey began because I wanted to know how it would look to fly a plane with the screen systems of the YF-19 in Macross Plus. So this part was particularly satisfying to me.

After carefully observing the reference drawings from the cockpit design, I decided I would model the inside panels, dashboard and chair, and then find a way to "project" what the outside of the fuselage looks like from the perspective of the pilot who is inside, thus creating the feeling of a transparent glass, looking out. Realism, baby.

Up to this point, everything I had modelled for this project came from very reliable Hasegawa blueprints and pictures of that same actual model assembled and shot from lots of different angles, so this was the first time I had to model something while making sense of the inconsistencies of each version.

So with enough material on my hands to test my modeling practice, I embarked on the new and exciting journey of dashboards, panels, HUD components and many, many test renders.

This section resumes my attempts at making convincing thruster effects, lights and smoke, heat and all that jazz.